Lost Confederate Treasure Discovery

Relic Hunting Team Announces Major Discovery in Graball, Georgia

by Michael Karpovage, May 22, 2022

Photo: Michael Karpovage

In the summer of 2020, as pandemic lockdowns shut down business and confined people to their homes, a group of historical researchers and relic hunters formed a team out of sheer boredom. Not knowing one another other than through social media and their love of history, Michael Karpovage, Kaaren Tramonte, Julia Preast, and Lee Dowdy decided to go after the most enduring legend in American history: the famed gold wagon train robbery of 1865.

They soon gained permission to explore private property near Graball, Georgia where local historians believed the crime took place. The team’s ultimate prize: a $20 Liberty Head ‘Double Eagle’ gold coin. Its provenance to the legend could fetch millions for just one coin, they speculated – a true treasure worth going after. It’s also one of rarest coins in American numismatics. Even more incredible is the history behind this legendary crime, the people involved, the conspiracy, betrayal, retribution, torture and imprisonment – not to mention a test of character for the team as they tried to keep the allure of finding treasure from consuming their personal lives.

“You guys have found more than the Oak Island guys have in 10 years.”

– Jim S., landowner.

A much coveted $20 Liberty Head 'Double Eagle' gold coin (example). These were pilfered by the highway robbers as much as their horses could carry. Finding just one of these coins was the ultimate prize for the relic hunting team.

THE MIDNIGHT RAID. The War Between the States, better known as the American Civil War, raged between 1861 and 1865, taking the lives of 600,000 Americans. It was the greatest rebellion the world had ever known. With brother fighting brother, our country was ravaged as the USA fought the Confederate States of America (CSA). The ramifications still divide our nation some 157 years later.

In the lawless weeks after the fighting ended, what would come to be one of the Civil War’s greatest mysteries was unfolding on a remote Georgia farm owned by a sickly widow named Susan Moss. It was the May 24, 1865 midnight raid of a wagon train that carried the CSA treasure specie of six private banks from Richmond, Virginia which had escaped the decimated capital of the Confederacy not a month before. The bank officials that accompanied the wagon train, along with their Union escorts, were on their way from Washington, Georgia back to Richmond, Virginia by way of a pontoon bridge over the Savannah River.

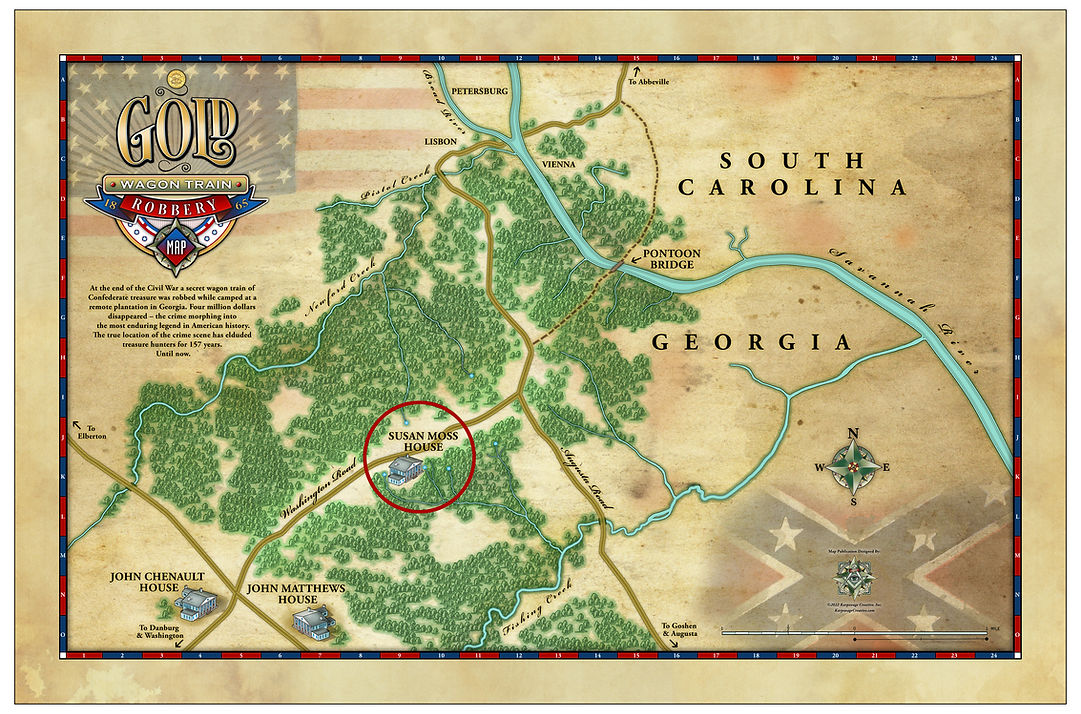

Gold Wagon Train Robbery Map designed by Michael Karpovage. Shows the general area where the Moss Plantation was once located between the Chenault Crossroads and the Savannah River in 1865 (present day Graball, Georgia). Somewhere on a horse lot near the main plantation home is where the wagon train robbery took place around midnight on May 24, 1865.

After traveling 18 miles from Washington, GA, darkness and exhaustion set in. But they were still 3 miles short of the river crossing. The last home on the road was the late David Mims Moss plantation house, occupied by his widow Susan Moss, her three children, her father Leiston House and sisters. It was Susan’s sister Mary F. (House) Lane who gave notarized eyewitness testimony in 1925 at the age of 80 to the events that unfolded in the summer of 1865. These events were also corroborated under oath by several of the bank officials involved.

Five wagons containing $450,000 in gold and silver coins, estimated to be worth over $10 million in today’s money, camped out in a gated horselot near some woods not 100 yards from the Moss house and just 50 yards from the old stagecoach road.

The train was insufficiently guarded by a mere seven Union cavalrymen. But stragglers from the Confederate army, living off the countryside, along with a few local men, knew about the treasure. Confederates who fought for four straight years believed they had a better right to the treasure than the Federals who controlled it. They conspired to shadow the wagon train since its departure from Washington, GA, waiting for the right moment to strike and reap their just rewards.

Word of the raid spread through national media. Here's a depiction of the ransacking of the Richmond bank gold and silver in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 7, 1865 edition.

Without a shot being fired, 20 highway robbers galloped into the camp, captured the sleeping escort party, teamsters, and bankers, and set about busting kegs and boxes open to pilfer the coveted treasure. Gold and silver lay glittering in piles ankle deep under a full moon as the thieves scooped up all they could carry in an intoxicating scene of greed and retribution.

The robbers then loaded their horses, split up, and hid their stolen loot nearby in secret locations to recoup later. They hid their stashes in tree branches, under old stumps and brush, under fence posts and bridges, and even in a creek baptismal pool of a local church. Others had the misfortune of having their old sacks or saddlebags split open because of the sheer weight of the treasure haul. A trail of shiny plunder followed in their horses’ wake as they plodded away to escape. Some of the culprits were never to be seen again – several of whom used their ill-gotten gains to become very wealthy businessmen out West.

Early the next morning after the wagon train departed in haste and made it across the Savannah River, farm servants on the Moss plantation discovered the horselot littered with $20 gold Double Eagles and Mexican silver dollars. They, in turn, grabbed all they could carry.

Here is a photograph of a typical military pontoon bridge at the time constructed by engineers. The same was built over the Savannah River to transport troops and supplies much faster between Washington, Georgia and Abbeville, South Carolina (both railheads) – a stretch of almost 40 miles of stagecoach road. The only other means was a slower ferry ride further up river at the Lisbon-Vienna crossing.

Most of the pontoon bridge was washed away by a severe storm some weeks after the robbery. Its location (shown on Karpovage's map illustration above) is based on an 1869 property estate drawing showing a "Pontoon Bridge" label over the river. The local land surveyor would have known where the bridge was based on roads leading to and from its location. And the fact that years after its construction it was still considered a landmark for a property map. The 1869 plat was discovered by Michael Karpovage and Michael Grafton while conducting research at the National Archives in Morrow, Georgia. The bridge location was a key element in determining how many miles away the Moss horselot would have been located based on eyewitness testimony.

At the behest of J.H. Weiseger, one of the victimized bank officials who stayed behind to recover the losses, a posse of armed citizens led by former Confederate Brigadier General Edward P. Alexander was able to recover a total of $110,000 that next day. $40,000 was found at the horselot itself ($10,000 of which former slaves had stolen). $70,000 was returned after confronting the guerrillas still in the area. That recovered $110,000 was placed in a vault back in Washington, GA and protected under Federal marshal law, its ultimate fate not decided until 1893.

When the pilfered treasure train finally reached Richmond, VA, $160,000 was in its coffers. With the addition of the $110,000 seized, $270,000 of the treasure was accounted for. That means of the original $450,000 on the wagons leaving Washington, GA, a net total of $180,000 ($4 million today) was either stolen or lost.

Bank of State of Georgia (ca. 1819) just off Washington, GA's public square where the $110,000 in recovered stolen coins was placed in a vault under Federal protection.

During the war, Dr. J. J. Robertson and his family resided on the second floor. Today, Regions Bank makes its home here, located at 100 E. Robert Toombs Avenue.

THE TORTURE OF THE CHENAULTS. In the following weeks, as word spread of the incredible crime, a vindictive former slave led a Union general to the Chenault plantation where some of the robbers had camped prior to and after the ambush. Union Brigadier General Edward A. Wild and his colored troops terrorized the prominent Chenault family to extract information on the whereabouts of the specie. The Chenault men endured brutal torture: being hanged by their thumbs with their arms behind their backs until they begged to be put to death from the excruciating pain. The Chenault women were stripped naked in utter humiliation by former servants, then falsely imprisoned in the local jail. The family dog was shot dead and bayoneted. The troops even stole what little personal gold and valuables the family did own. Yet, no family member knew the whereabouts of the loot and no stolen treasure was ever found on the Chenault plantation. Wild’s reign of terror swept up and down the roads from Washington, GA to the Savannah River until he was recalled to Washington, D.C. and mustered out of service after the fervor he had caused.

In the end, no one was ever officially arrested or convicted of the robbery.

Stolen or lost, the treasure was subsequently buried to history. But not to legend.

Union Brigadier General Edward A. Wild

Engraving from Harper’s Weekly shows Union troops searching for buried treasure on a southern plantation.

THE MYSTERY. Because of General Wild’s brutality, the Chenault Plantation House – still standing today and on the National Register of Historic Homes – has forever been wrongly identified as being the scene of the famous wagon train crime. For years after, treasure hunters flocked to this incorrect location and the myth grew, but people always came away empty-handed. Armchair treasure hunters then perpetuated the myth by repeating the same bad information on the Internet. Even the current owners of the Chenault House are considering a sign that reads ‘No Treasure Here’ to ward off the steady stream of door knockers.

However, if previous treasure hunters had dug deep enough into research, they would have found eyewitness testimony under oath and even personal accounts in the news of those claiming to be participants in the crime. Their stories consistently placed the crime scene at the Moss farm just up the road closer to the river in the general area of the present day Graball intersection. The banker Weiseger said they camped just three miles from the pontoon crossing that fateful night.

The original Moss plantation home looked exactly like the present day Chenault, Matthews (shown above), and Sale houses still standing today. There were four similar family plantation homes built from 1854 to 1859 within a six mile radius of the Chenault home by a contractor/carpenter from Macon, Georgia named John Cunningham. They were in the Greek Revival style with a two-story, five-bay portico supported by six fluted Doric columns.

Photograph of the Moss family cabin they lived in after facing financial ruin from the destruction of their plantation home burning in 1866. This one-story claboard structure was later known as the Quinn Dallis home and appeared in the 1976 book The Fate of the Two Confederate Wagon Trains of Gold by Ralph L. Hobbs. The cabin does not exist today.

The mystery remains: where exactly along the Old Washington Stagecoach Road was the original site of the burnt down Moss plantation home located? If you find that, you can the piece together the clues of where the fenced-in horselot would have been, and thus pinpointing the site of the wagon train robbery itself.

No one on historical record had ever found a coin from the true treasure location: the Moss farm horselot. The main plantation home burned down in 1866, a year after the widow Susan Moss died. The Moss family was too financial destitute after the war to rebuild. The remaining family lived in a one-story ramshackle cabin – a true fall from the grace from their earlier antebellum days.

In essence, the original Moss homesite vanished with time and had never been re-discovered. The horselot was approximately 100 yards away from the home according to bank officials who were robbed that night. In and around that horselot is where many of the dropped or missing coins, including ‘Double Eagles,’ could still possibly be lost to time. The challenge in finding it is the sheer landmass. The original Moss plantation was made up of 1,600 acres in the 1860s and has long been parceled off to various private landowners.

From left to right:

Michael Karpovage, Lee Dowdy, Kaaren Tramonte, and Julia Preast celebrating with some whiskey after digging up the CSA tag and first silver Mexican coin.

Photo by Michael Karpovage.

THE DISCOVERY. Fast forward to July 2020: Michael Karpovage made contact with Washington, Georgia Museum Director Stephanie Macchia, researcher Marshall Waters III, Ph.D., and Bob Young, author of Graball Road, all experts on the subject. Karpovage, a cartographer by trade and an author of a treasure hunting book series called The Tununda Mysteries soon found himself like a character in one of his books. He formed the organizational backbone of the relic hunting team, delved deep into research, compiled a slew of old maps, and secured key permissions. Kaaren Tramonte brought her knowledge of historical real estate transactions and architectural preservation. Lee Dowdy, a plumber by trade, brought expert metal detectorist skills along with his assistant Julia Preast. The team wanted to approach this mystery as a historical forensic investigation and of course hopefully hit it big in the process.

On July 14, 2020 while exploring a horselot at night due to a 106° heat index during the day, Karpovage, Tramonte (and her 8-year old son), Preast, and Dowdy soon found themselves in their own intoxicating midnight scene reminiscent of the actual ambush. Under the glare of flashlights swarming with bugs, and with iPhones recording, Dowdy’s metal detecting expertise paid off. Big time. Here are their finds in chronological order of discovery:

Photo by Michael Karpovage.

The CSA Name Plate: An immediate hit on Dowdy’s Minelab CTX 3030 resulted in a rusted metal tag or name plate engraved with ‘CSA.’ It sat on top of soft crumbling wood, possibly used on a wooden box or keg in the wagon train. This was an astounding first find because it placed an item from the Confederate States of America on the old Moss property. Since the area wasn’t a plowed farmfield for crops, the soil in the fenced-in grass feedlot was never overturned. After using his pinpointer to further check the hole, Dowdy received another hit.

The First Silver Mexican Coin: A few inches below the nameplate, Dowdy extracted a shiny 1855 Mexican silver 8 Reale coin. The team was blown away. This was their once-in-a-lifetime moment and their raw emotions were caught on camera – since dubbed ‘The No F---king Way!’ video. Having never pulled silver from the earth, they were quite surprised the sheen was in such a pristine condition. After all, it was never exposed to the air, which oxidizes or darkens silver over time.

Photo by Lee Dowdy.

The Bronze French Coin: Later around 2:30 am, in a gully while the rest of the team cooled down in Karpovage’s air-conditioned truck, Dowdy drew on his years of experience searching dried up creek beds. He received two side-by-side signals on his detector. He dug the first target which was in very hard ground and it came out in a clump. He couldn’t break it open with his hands, so he placed it in his pouch to inspect later to focus on his next target. And subsequently he had forgotten that clump in light of what he found next. That clump was broken apart a month later while alone at his house in Alabama when he happened to clean out his bag. It revealed an 1855 French Cinq Centimes bronze coin – more evidence of the presence of foreign denominations supporting statements by officials who said foreign coinage was included in the bank reserves.

The Belgian Lefaucheux Revolver: When Dowdy started digging the second

target, an outline of the top of a pistol was exposed. He immediately yelled for the

others to come and see before digging further. He shouted to no avail, and then used

his cell phone and called Karpovage in sheer excitement. Karpovage was with Tramonte and her son cooling

down in his truck. He left the boy with his mother and immediately started recording with his phone as he met

Dowdy just past a fenceline. Dowdy guided him down the slope of a gully with his flashlight. In the bank of the gully they immediately saw the shape of the cylinder where bullets were fed into a revolver. They dug out the specimen and could not believe their find. Later it would be identified as an M1858 Belgian Lefaucheux pin-fire revolver with the tip of its barrel broken off. It was a military model sidearm with a lanyard ring that both the CSA and USA forces used.

Photo by Michael Grafton.

Photo by Michael Grafton.

The Second Silver Mexican Coin: After further examining the target hole, Karpovage saw a flash of silver about five inches away. They pulled out another Mexican silver dollar. This time it was an 1862 Mexican 8 Reale coin with a hole in it. A hole was commonly used to sew a coin into clothing to hide, or worn around the neck for safekeeping, or even possibly tied to the lanyard at the bottom of the revolver’s grip.

Photo by Michael Karpovage.

The Third & Fourth Silver Mexican Coins: At 3 am the team had turned in for the night. Around 4 am, Karpovage received a phone call in his guest room at the landowner’s main house. It was Tramonte and Dowdy telling him to come meet them at the guest cottage as more coins were found. Just before Dowdy and Preast had gone to bed they decided to do spot detecting in the field behind the cottage. They had found two more silver Mexican coins, both 1855 2 Reales, thin and heavily worn.

The ‘head’ and ‘tails’ sides of all the coins found were scratched considerably due to the sandy soil they shifted in for the last 155 years. However, the scaring also gives them a true uniqueness and personality that forever connects them to their provenance.

Photo by Michael Karpovage.

At that point emotions changed. Exceeding all expectations, the team’s excitement was replaced by seriousness as they knew their lives were changed forever and things were going to get real complicated.

The team described their discovery like a debris trail from a shipwreck on land and hoped their finds would lead them to the hull – the main spot where piles of coins were left behind.

“The Mexican coins found are consistent with the type of coins listed in the Spinner [CSA Treasurer’s] inventory, and coins left unaccounted for based on Weiseger’s count. I believe we now have a preponderance of evidence supporting the location of the feedlot where the robbery occurred, and linking the coins to the robbery itself. What remains now is finding what else was left behind! Research never ends! Congratulations, all!”

– Bob Young, author of Graball Road.

Because of this initial discovery proving local historians’ theories correct, the team landed a private contract and exclusive access to the land owned by the great great granddaughter of Susan Moss. In fact, that direct descendant originally had no idea the history that had taken place there in the waning days of the Civil War. When she first read of her relative Mary (House) Lane’s 1925 testimony she thought it was a joke.

Preast and Dowdy departed the team shortly after due to personal reasons, but Karpovage and Tramonte added veteran brother relic hunters Tom and Randy Burroughs, plus explorers Michael Grafton and Brian Miller. On several occasions the team was competing with ‘land pirates’ brought in by a greedy Yankee lawyer they dubbed ‘My Cousin Vinny.’ At one point the treasure poachers were caught on hidden surveillance cameras trespassing. After a confrontation they did admit to digging on the team’s claim. Another time things got a bit hairy when armed deer hunters rolled up on the relic hunters, but peace and cooperation soon prevailed and they became an on-site de facto security force.

“When you find treasure, a person’s character really comes to the surface. Greed, envy, lust, and pride – four of the seven deadly sins – were suddenly thrust upon us. And it’s an ugly thing to experience face-to-face.”

– Michael Karpovage.

From left to right:

Michael Karpovage, Michael Grafton, and Brian Miller after finding a US cavalry horse bridle rosette on adjacent land.

Photo by Michael Karpovage.

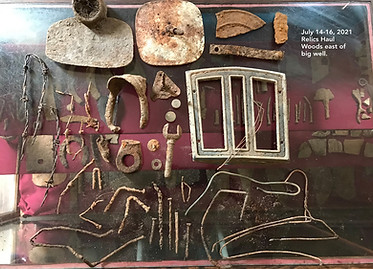

One year later on July 16, 2021 Karpovage, Grafton, and Miller – having purchased their own Minelab CTX 3030 detectors – dug up a Union cavalry horse bridle rosette on an adjacent property not too far off the main road. Was the rosette from the Union cavalry who had originally escorted the doomed wagon train or was it from Wild’s troops tearing up the countryside weeks later? Regardless, this incredible find proves again all of the evidence being unearthed continues to fit the stories. Despite digging up over 300 sundry farming relics, no more actual treasure coins have been discovered to date.

Ultimately, the wheels fell off the original relic hunting team’s own wagon in early 2022. Karpovage and Tramonte parted ways as of the 157th anniversary of this legend. Despite the break-up, Karpovage, who lives in Roswell, GA closest to Graball, has renewed vigor to someday hold that elusive ‘Double Eagle’ in the palm of his hand. He believes the mystery won’t finally be solved until gold is reunited with silver.

THE END

On display at the Washington, GA/Wilkes County Museum are hundreds of farming relics pulled from the site. Karpovage is also looking to create an educational scale model diorama with the museum to depict this legendary wagon train ambush. And he is currently working on a YouTube historical documentary of this mystery/discovery using the actual silver Mexican coin, the Lefaucheux revolver, and the US horse bridle rosette. The French coin remains with Lee Dowdy. The 1855 8 Reale, (two) 1855 2 Reales, and the CSA engraved tag remain in ‘My Cousin Vinny’s’ greedy grasp.

Michael J. Karpovage is a Loreist. These types of treasure hunters engage mainly for the history and lore and can be the most passionate in their approach and motivation. But they are totally fine if they never make a recovery. They just love the pursuit of solving a mystery or engaging in an investigation because it's all about the adventure. It's about being outdoors with fellow enthusiasts, meeting people from all walks of life, doing the heavy research, documentation, and forensic work. And most importantly, the thrill of discovery . . . that "Wow!" moment.

For inquiries, contact Michael HERE.